Aint It Funny Danny Brown Clean

In 2013, Danny Brown sparked a minor hip-hop beef when he said about fellow Detroit rapper Big Sean: "You listen to how I talk about Detroit, and you listen to how a rapper like Big Sean talk about Detroit, and it's like we're talking about two different cities. Which is probably true, because Detroit is that type of city — he went to the best high school in the city, you know, he probably was real spoiled or sheltered, so it's like two different worlds."1 More than a slight to Big Sean's credibility, Brown captures how the ways we interpret, understand, and diagnose Detroit — one of the most economically and racially segregated cities in the US — is contested and political. Detroit is "that type of city," a city that is simultaneously multiple and type-casted, imaginary and real, going to work and having no work, resurgent and resilient and yet in decline, beaten down, and depressed.

These descriptors of Detroit also apply to Danny Brown, and understanding one lays bare the stakes and the limits of understanding the other.2 In his 2016 album Atrocity Exhibition, Brown confronts his anxiety, depression, and self-destructive drug addiction, as well as how his self-destruction is a crucial piece of the magnetism that attracts his audience's gaze. As Brown explains, the title is a nod to Joy Division's song of the same name because, "[Ian Curtis is] talking about how he feels like he's part of a freak show almost. People just wanna come see him and they just wanna see him be a certain type of way. I totally relate to that. That's just how I felt with this album, 'cause a lot of people expect for me to be some crazy drugged-out I-don't-know."3 The four music videos that accompanied the album each apply a unique remix of the horror aesthetic: from Saw-like torture scenes to glitchy found footage and drug-induced paranoia. My primary focus here is on "Ain't It Funny" (dir. Jonah Hill), in which Brown is trapped in an all-white sitcom.4 These visual representations of horror attach Brown's lyrical narratives of depression to a historically-situated, material, and racialized setting: the city of Detroit. At this compelling intersection, Brown confronts viewers for their complicit relationship to not only the ruination of Detroit, but also to his inseparable physical and mental health breakdown.

Rolling Stone describes Brown's music as a combination of "Raekwon, early Björk, Joy Division, Talking Heads, and System of a Down'sToxicity," but, to me, the experience of Danny Brown feels otherworldly.5 Brown has multiple voices, including what's been described as a "high-pitched squawk" that has become his primary rapping cadence.6 He uses this unique voice to overpower loud and discordant beats, featuring heavy horns, electronica, and deep bass. His visual style, perspective, humor, and turns-of-phrase are compelling alone, but part of his allure is his indescribable strangeness, including the perception of his destructive lifestyle; as he jokingly put it, "people think my life is just non-stop orgies with crackheads. And it kind of is."7 Similar to witnessing the spectacle of Kanye West — absent the political meltdown — watching Danny Brown over the past several years entails admiration for his musical and imagistic brilliance and a disturbing attentiveness to his deterioration. In this sense, Brown, and the voyeuristic fantasy fans project on him, parallels Detroit, a city whose ruins are commercialized, admired, and consumed.

Historically, Detroit has served as much as a symbol — of manufacturing and the American dream, of urban decay and post-industrialization, of rebirth and the American comeback — as an actual place. Its nicknames tend toward hyperbole, and weld its contributions to capital with its contributions to culture: "Paris of the Midwest," "Arsenal of Democracy," "Motown," "Motor City," and "Murder City." Of the most recent Detroit stories, John Patrick Leary delineates three categories: Detroit as a metonym for the car industry, manufacturing, and unions; as "Detroit Lament," wherein its decline is fetishized, most famously in the widespread consumption of photography of Detroit's abandoned buildings and "ruins"; and as "Detroit utopia," wherein the city is conceived as a "blank canvas" for a limitless future of boutiques and urban farming (see: the documentary Detropia).8

After Brown's first album in 2011, he quickly became a quasi-ambassador for the city in several such stories. When niche, alternative and even commercial media outlets wanted to tour Detroit, they asked Brown to be their guide.9 A tour of Brown's Detroit is a tour of empty space. Much of what he has to show are the charred remains of the buildings of his childhood, a phenomena he describes in the refrain of one of his early songs, "And where I lived, it was house, field, field. Field, field, house, abandoned house, field, field."10 Brown showcases Detroit with love, but breaking from the popular trend, he paradoxically keeps the city and its fetishization at arms-length. As he says, "Nah, I'm not doing it for none of them motherfuckers. I'm doing it to get away from them. Fuck all that. Fuck the hood. Fuck Detroit, bruh. Detroit ain't who I am."11

Brown's grim and often surreal stories about growing up in Detroit make his refusal to fetishize understandable. And yet, it is surprising to hear Brown say "Detroit ain't who I am." One might expect him to identify with the strength, grit, and resilience attributed to Detroiters, vaguely universalized and transhistorical though this stereotype is. The mottos "Detroit Hustles Harder" and "Detroit vs. Everybody," promoted by an Eminem song featuring Brown, are found on popular t-shirts in the city. But these interpretations of Detroiters oversimplify the impact the city's symbolic function has on its primarily Black residents and their psychic life.

Detroit offers a poignant example of a wider stigmatization of Black mental health, experienced variously by Black men, Black women, Black activists, and members of the Black LGBTQ community.12 (Currently in Detroit, for example, there is an epidemic of violence against Black transgender people.)13 Across his interviews, Brown shares his experiences with violence, drug dependency, incarceration, and racial terror, but situated among Detroit grit and grind stories, his depression is somehow unanticipated, and can be seen as a weakness antithetical to and inexpressible as a condition in the city. That his celebrity forces him, like a ghost, to always return home helps us understand why horror is Brown's chosen visual register for Atrocity Exhibition, an album about his struggles with mental health.

In film, Detroit has long been used as the setting for post-apocalyptic hellscapes, most famously in Robocop (1987). Recently, Detroit has become a preferred setting for horror films, perhaps because the apocalypse permeates the present and we no longer need to imagine our futures through Detroit because Detroit is already everywhere. Viewers in just the last five years have become accustomed to the Detroit horror aesthetic in (white-centric) movies like Only Lovers Left Alive (2013), It Follows (2014), Lost River (2014), and Don't Breathe (2016). Danger lurks around every corner of emptied-out industrial husks (some overtaken by nature, others converted to high-priced lofts), under highway overpasses covered in graffiti, near beautifully aged Art Deco architecture from the 1920s and 1930s with missing windows, and beside boarded-up two-and-three-story brick homes with gorgeous Pewabic-tiled fireplaces. Detroit horror has a muted color palette: high, overcast skies reflected on salt-stained streets; wet, potholed concrete shining in the black of night. Detroit horror has a sound: screams or gunshots that ring out across abandoned lots; footfalls muted by a heavy snow. Some of these movies took advantage of Michigan's steep tax breaks for film production companies — which belong to a long line of big industries that were to supplement the jobs hemorrhaged by the automotive industry — and others, like Don't Breathe, use a few establishing shots of Detroit before reproducing the aesthetic elsewhere, corroborating former mayor Coleman Young's quip that "Detroit today is your city tomorrow."14 The truth of this statement, I contend, makes Detroit an effective setting for contemporary horror, despite the "Detroit comeback" narrative. At the same time, the compensatory function in having a "there" where bad things happen so viewers can feel a bit better that they are in a slightly less awful "here" is the source of Detroit's usefulness. Detroit horror condenses in its aesthetic the gesture of acknowledging and disavowing post-2008 American decline writ large.

Brown's Detroit horror is more historical, racial, and site-specific than that of these movies. To build his counternarrative, Brown's music videos avoid the recognizable downtown and midtown sites of so-called "revival" and gentrification, opting instead for the unremarkable, open spaces of parking lots and fields. In "Pneumonia," Brown hangs by chains extending endlessly into the sky, controlled by unseen forces, and is tortured in an empty parking lot — suggestive of the unfulfilled promise of Detroit's overinvestment in the automotive industry. His torture is interrupted with clips of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, and with Brown's own DIY political advertisement, calling on the active participation of those in power in the perpetuation of Detroit's horror. In "Lost," Brown deconstructs the fantasy elements of horror the movies rely on, applying their visual tricks of surveillance and paranoia to the horror of drug addiction and buying and selling drugs in a Detroit apartment building. In his music video "When It Rain," Brown flips the generic expectations of Detroit horror. In the first two-thirds of the video, the viewer watches through a glitchy VHS filter a montage of dancers filling the familiarly abandoned fields, convention halls, and basements with sublime vitality. In the final third, Brown pops the VHS tape out of its player and makes his way down multiple levels of the recognizable Detroit home we expect to be empty and haunted until he steps out onto a cracked stoop and into a front lawn where a group of his friends are cool-posing, dancing, and laughing.

Brown moved to the suburbs as soon as he could, first to Royal Oak and then farther out to Farmington Hills. In light of this move, I interpret the final and beautiful scene of "When It Rain," with Black men experiencing joy on a Black homeowner's front lawn, as Brown's humorous and self-aware nod to what horrifies his new suburban white neighbors. I also see his move as offering a way into the disturbing video "Ain't It Funny," which indicates that one cannot understand Detroit nor Danny Brown without taking into account the frightening specter of the suburbs.

A dark predecessor to Jay-Z's star-studded music video "Moonlight," which parodied Friends, "Ain't It Funny" shows Brown trapped in an all-white sitcom, broadcast on "The Religious Values Network." In the video, Brown plays "Uncle Danny" and is joined by Gus Van Sant (Milk) as "Dad," Joanna Kerns (Growing Pains) as "Mom," Christina Applegate-look-alike Lauren Avery as "Daughter," and "This Fucking Kid" as "Kid." Uncle Danny's cries for help are muted and subtitled, silenced by Danny Brown's lyrics and the sadistic laughter of the all-white audience. For the white characters in the sitcom, "Uncle Danny" is there to patronize or have sex with, while for the white audience he is simply the butt of the Kid's catchphrase: "Oh Uncle Danny!" The sitcom cuts in and out of Brown's drug-induced hallucinations, in which he fantasizes about murdering "Mom" and "Daughter," with mascots of prescription drugs standing watch.

On the surface, "Ain't It Funny" satirizes the trope that Black men in sitcoms must be unthreatening, often as adoptees into, and thereby saved by, white families — think Gary Coleman in Diff'rent Strokes or Emmanuel Lewis in Webster. In a reversal of these shows, Uncle Danny punctures the safety of the white sitcom by embodying the racist trope of the hyper-sexualized and violent Black man, a stereotype that Brown faced after a white female concertgoer infamously attempted to perform oral sex on him during his performance. Uncle Danny's sexuality enters the foreground when he confronts Mom about acquiring an STD — using the language of an unplanned pregnancy. She says, "I don't know what to tell you, it's not mine." He dazedly responds, "But you're the only person I've been with," which receives raucous laughter from the white audience, including a close up of a woman disturbingly licking her lips. These scenes are juxtaposed with the most unsettling visual in the video, repeated over and over again: Uncle Danny's hallucinatory fantasy of himself in bed with Mom and Daughter covered in blood.

"Ain't It Funny" brings to mind what Kinohi Nishikawa describes as hip-hop satire:

Unlike the high-minded, dead-serious music of "socially conscious" artists, hip-hop satirists have taken refuge in the comic mode as a means of undoing authenticity's hold on African American culture. Their efforts have led to the development of a growing, if still inchoate, field of hip-hop satire: a subgenre that advances the funniest, and often most profound, critique of rap's investment in "keeping it real."15

But here, Brown's satire belongs strictly to the video. The lyrics could not be more dead-serious. They document Brown's depression and addiction to a cocktail of different prescription drugs including Adderall and Xanax as well as cocaine and alcohol. Against the hip-hop clichés that glorify the drug trade, the song describes, "The flow house of horror/Dead bolted with metal doors." Brown attributes his addiction to survivor's guilt, "Live a fast life/Seen many die slowly/Unhappy when they left/So I try to seize the moment." Brown's frenetic energy cannot break him out of this house of horror. The song ends with resignation: "Can't quit the drug use/Or the alcohol abuse/Even if I wanted to/Tell you what I'm gonna do/I'ma wash away my problems/With this bottle of Henny/Anxiety got the best of me/So popping them Xannies." The tension between the forcefulness of his voice, the blaring horns, and the despondency and hopelessness of the narrative make "Ain't It Funny" a deeply personal and painful song set against the satirical rendering of a sitcom.

Whereas Detroit is now a preferred setting for horror in American cinema, the Detroit suburbs have long been integral for the cultural imaginary of an idealized America, serving as the setting for sitcoms about mostly affluent, mostly white families, including Home Improvement, 8 Simple Rules, and Freaks and Geeks. In these shows, the safe settings free up families to learn feel-good life lessons and grow together; danger is merely comical, like when Tim Allen repeatedly electrocutes himself with overcharged power tools. The two Metro Detroit sitcoms that featured African American protagonists, Martin and Sister Sister, also capture the racial and economic contradictions of Detroit. In one telling example from Sister Sister, "Mo' Credit, Mo' Problems" (S5 E11), Tia and Tamera get lost in downtown Detroit because the freeway ramp is closed — the freeway is a crucial escape valve for suburbanites — and their car breaks down. When a young man attempts to help them, the twins frantically debate if he "wants to murder us" or "probably just wants to rob us," but ultimately accept his assistance and learn the lesson that (Black) Detroiters are in fact people too. Against Detroit horror films, and revising the Detroit suburbs sitcom, Brown's music videos suggest that the suburbs are where horror actually happens.

Brown's clearest articulation of "Ain't It Funny"'s title links his depression with the fantasy of achieving the good life and making it to the suburbs: "Octopus in a straight jacket/Savage with bad habits/Broke serving fiends/Got rich became a addict/Ain't it funny how it happens/Who would ever would imagine." Though the clearest reference to the suburbs, this verse is edited out of the music video and replaced with a segment of the live sitcom. In this interlude, "Dad" walks in on Uncle Danny while he is urinating on a vase of flowers and family portraits in the living room. When Dad asks why he's doing this, Uncle Danny explains, "I've been destroyed and if I destroy maybe I'll feel okay." Dad responds, "None of us feel okay," and "the Kid" breaks the tension with his classic "Oh Uncle Danny" line before the his eyes turn into lasers and we return to Uncle Danny's murder fantasy. The very moment in the song's lyrics that document Brown's particular Detroit rags-to-riches story, which implies his departure from the city and into the suburbs, is substituted with an appeal to the universal: "none of us feel okay." Within the song, Brown is sensitive to the ways that his depression is part of a broader historical attunement with others, rapping "It's a living nightmare/That most of us might share." But he follows this immediately with the lines "Inherited in our blood/It's why we stuck in the mud," which I interpret as referring to the affective experience of Black Americans, and not someone like Dad. The sentimentality of the white suburban sitcom, which presumes to speak for a universalized "America," is shown to be not only ineffective in treating Uncle Danny's sickness, but an active agent in exacerbating it.

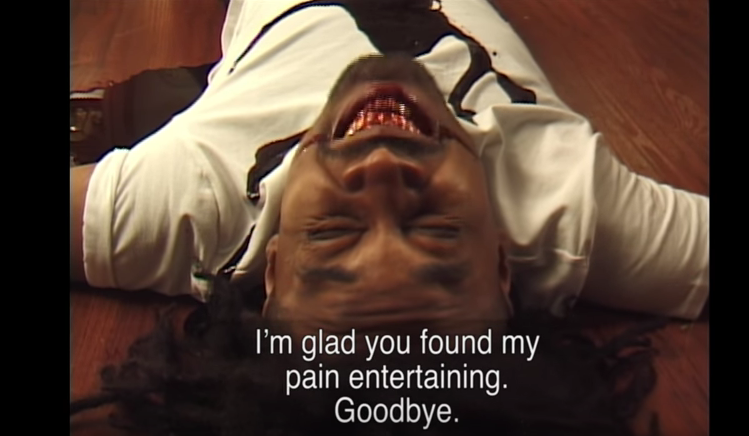

Through its deployment of the suburban sitcom, the music video adds a metafictional layer to the song's lyrics that aggressively implicates the (white) audience in Brown's addiction. Silenced by the audio of both the song itself and the laughter of the all-white audience, Uncle Danny's pleas for help are restricted to subtitles, "I have a serious problem. Please stop laughing." At the conclusion of the video, Uncle Danny re-directs his plea away from the white audience and toward the large mascots of prescription drugs, smiling as he says, "You guys are my only friends. I need you." The mascots proceed to stab and kill Uncle Danny, and the Kid joins him in breaking the fourth wall to condemn the audience, saying, "He's DYING and you people are LAUGHING. You DISGUST me." Over the final refrain of "Ain't it? Ain't it funny how it happens? Ain't it?" Uncle Danny's last words (again subtitled) are "I'm glad you found my pain entertaining. Goodbye."

The video shifts the meaning of "ain't it funny" from being about Brown becoming an addict after leaving Detroit and moving to the suburbs to being about the way (white) audiences' primary engagement with him is as a spectacle to consume, much the way audiences all too often consume and discuss Detroit. Put together, the song and music video hold in tension the actual, racial materiality of Detroit with the burden of its symbolic significance on the psychic life of individuals who live or have lived there. By admonishing his audience, Brown asks them to do the much more difficult work of conducting an honest reckoning of not only what they gain from their mediated relationships with Detroiters, but their complicity in the racism and economic inequality that generate physical and mental health crises. "Ain't It Funny" reconstitutes for contemporary listeners a relationship and responsibility to Detroit horror, perhaps captured best decades ago in an urban blues song used by Detroit's League of Revolutionary Black Workers in 1969-1970, "Enough! America, we don't mind working, but we do mind dying."16

References

Source: https://post45.org/2019/04/aint-it-funny-danny-brown-and-detroit-horror/

0 Response to "Aint It Funny Danny Brown Clean"

Post a Comment